Shock waves are thin regions within a flow where abrupt and irreversible changes occur in flow properties such as pressure, temperature, density, and velocity. These discontinuities arise in compressible flows when the local Mach number exceeds unity, preventing upstream propagation of information. To accommodate such high-speed disturbances, the flow adjusts through the formation of shock waves, fundamentally governed by the conservation laws of mass, momentum, and energy.

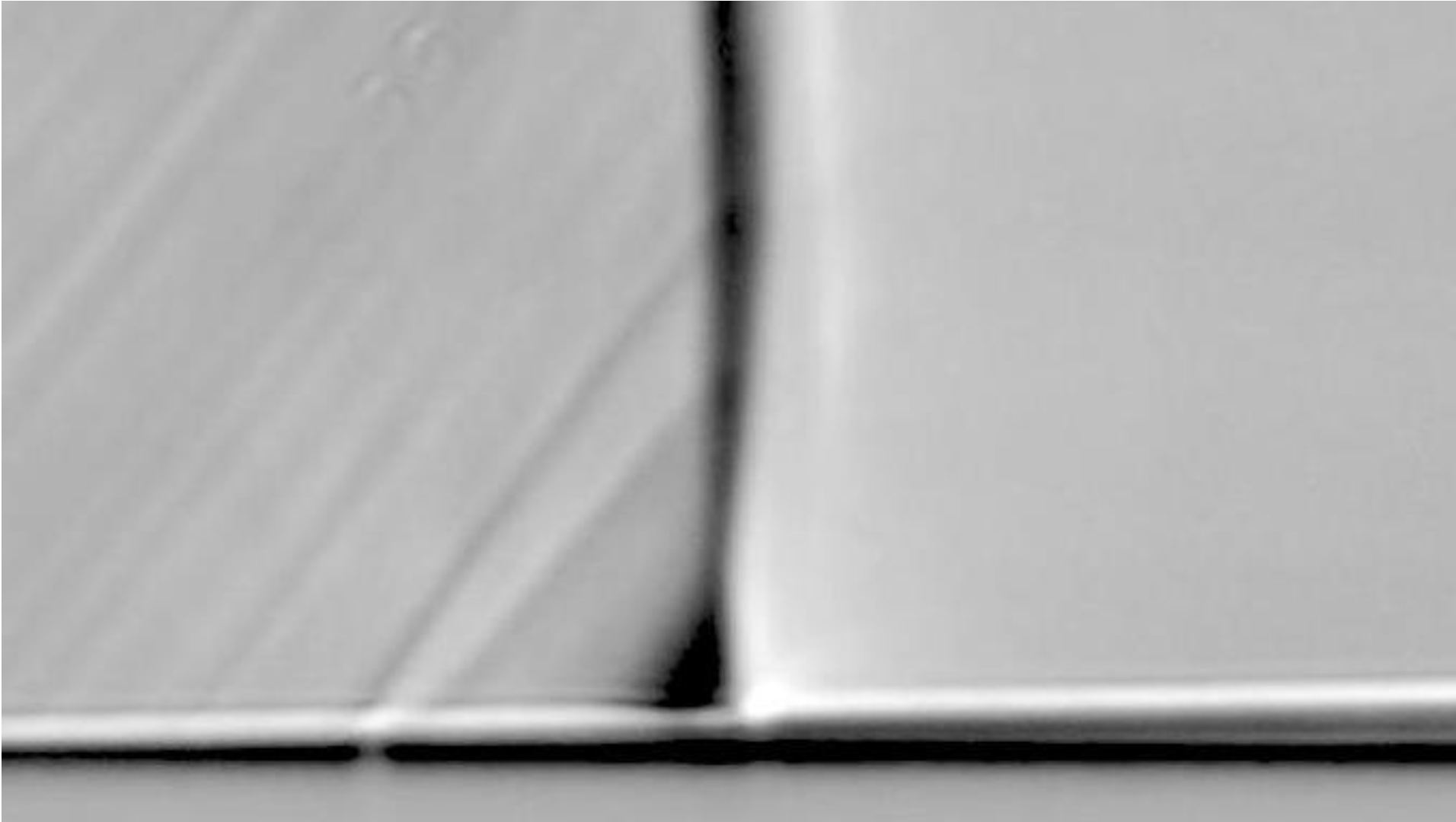

1 .Normal Shocks

A normal shock is a shock wave that is perpendicular to the direction of the flow. It is the most fundamental form of shock and serves as the basis for one-dimensional shock analysis.

- Occurs in ducted flows or symmetric configurations.

- Always results in a transition from supersonic to subsonic flow.

- Associated with significant increases in pressure and temperature, and a decrease in Mach number.

- Governed by the normal shock relations, derived from the conservation equations.

Figure 1:Schlieren images of normal shock wave turbulent boundary layer interactions attached at , Davidson & Babinsky (2018)

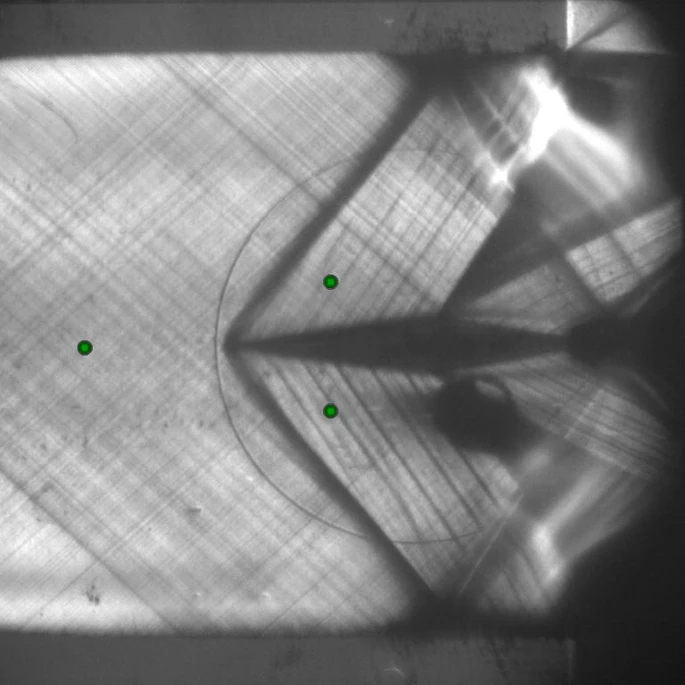

2. Oblique Shocks

An oblique shock occurs when the shock front is inclined at an angle to the oncoming flow. These arise in external flows over wedges or in internal duct flows where turning occurs.

Flow deflection occurs across the shock.

The upstream flow remains supersonic after the shock if the shock is weak and the deflection angle is small.

The shock can be attached (pointing from the surface) or detached (ahead of blunt bodies).

Governed by the θ–β–M relation, where:

- θ is the flow deflection angle,

- β is the shock angle,

- M is the upstream Mach number.

Figure 2:Schlieren visualization of the oblique shock by Zocca et al. (2019)

3. Bow (Detached) Shocks

When a blunt body moves at supersonic speeds, the shock wave cannot remain attached to the body. Instead, a bow shock or detached shock forms ahead of the object.

- Common in blunt-nosed launch vehicles or capsules.

- Results in a strong shock structure with high entropy generation.

- The stagnation point at the body surface experiences the highest pressure and temperature.

Figure 3:Bow shocks form whenever a flow travels faster than the speed of sound, whether in air, water, or even plasma. In this case, we see the striking LL Orionis bow shock in the Orion Nebula. Here, the powerful stellar wind from LL Orionis collides head on with the slower moving nebular gas, creating a curved shock front. This dramatic interaction was captured by the Hubble Space Telescope in 1995, revealing the beauty of astrophysical shock waves on a cosmic scale.

Photograph: NASA

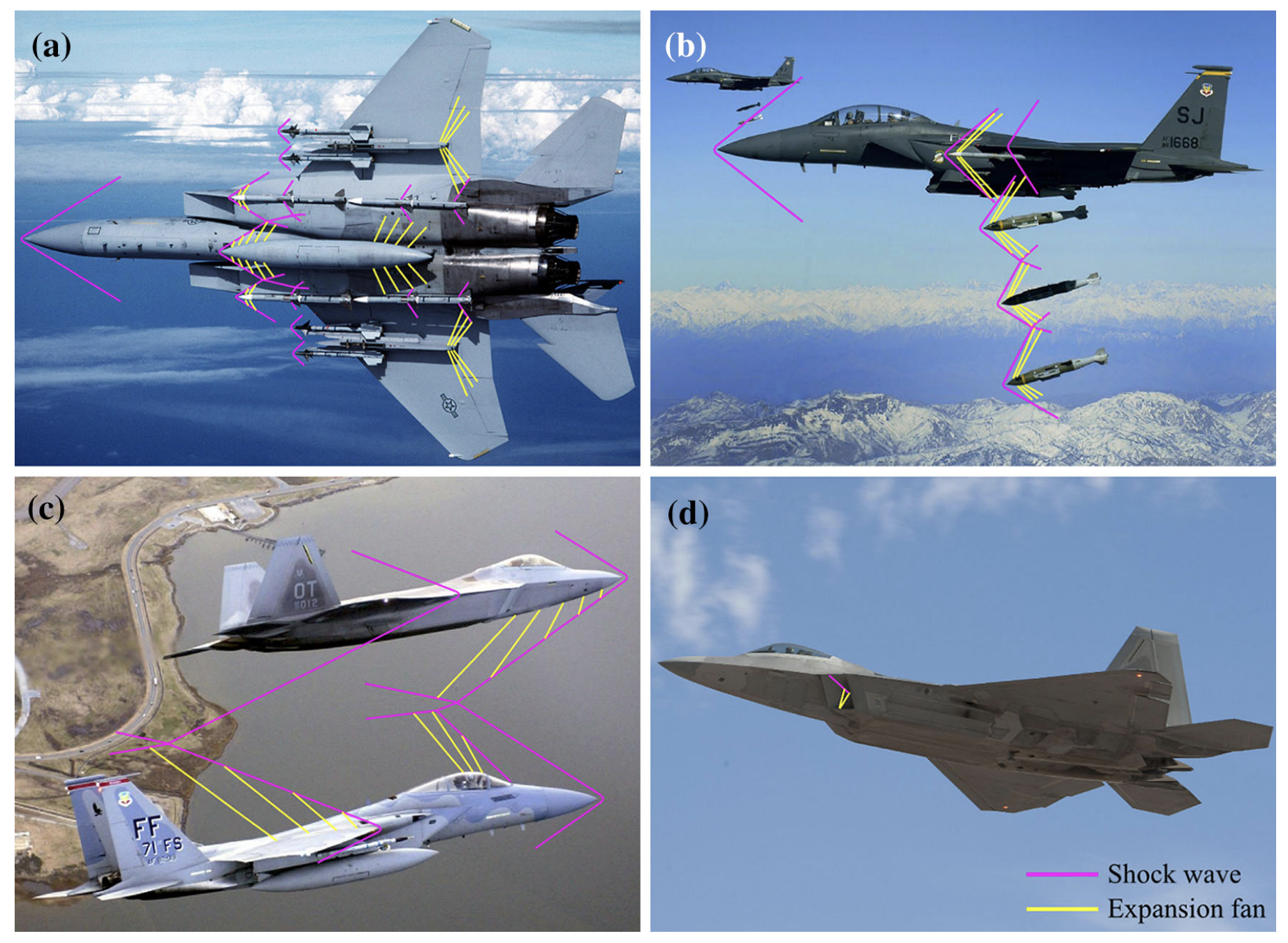

4. Expansion Fans (Not Shocks, but Related)

While not technically shocks, Prandtl–Meyer expansion fans are another form of compressible turning flow.

- Occur when supersonic flow turns around a convex corner.

- Flow accelerates and Mach number increases.

- Entropy remains constant; expansion is isentropic.

Figure 4:Illustration of practical applications in aerospace where an expansion fan/shock wave interaction arises: a store carriage, b store release, c formation flying and d engine inlet design Nel et al. (2015)

5. Shock–Shock Interactions

When multiple shock waves intersect, their interaction can result in complex wave structures:

- Regular reflection: Oblique shock reflects at a wall forming another oblique shock.

- Mach reflection: At higher Mach numbers or deflection angles, a third, stronger shock called a Mach stem forms between incident and reflected shocks.

- These phenomena are particularly important in supersonic inlets and high-speed impact dynamics.

6. Shock Classification by Strength

Shocks may also be categorized by their strength, determined by the pressure ratio or Mach number change across the shock:

- Weak shocks: Small change in flow properties; often found in small deflection oblique shocks.

- Strong shocks: Large property changes; typically occur near blunt objects or at high Mach numbers.

- Hypersonic shocks: Associated with Mach numbers > 5; often lead to dissociation, ionization, and real gas effects.

- Davidson, T. S., & Babinsky, H. (2018). Influence of boundary-layer state on development downstream of normal shock interactions. AIAA Journal, 56(6), 2298–2307.

- Zocca, M., Guardone, A., Cammi, G., Cozzi, F., & Spinelli, A. (2019). Experimental observation of oblique shock waves in steady non-ideal flows. Experiments in Fluids, 60(6), 101.

- Nel, L., Skews, B., & Naidoo, K. (2015). Schlieren techniques for the visualization of an expansion fan/shock wave interaction. Journal of Visualization, 18(3), 469–479.