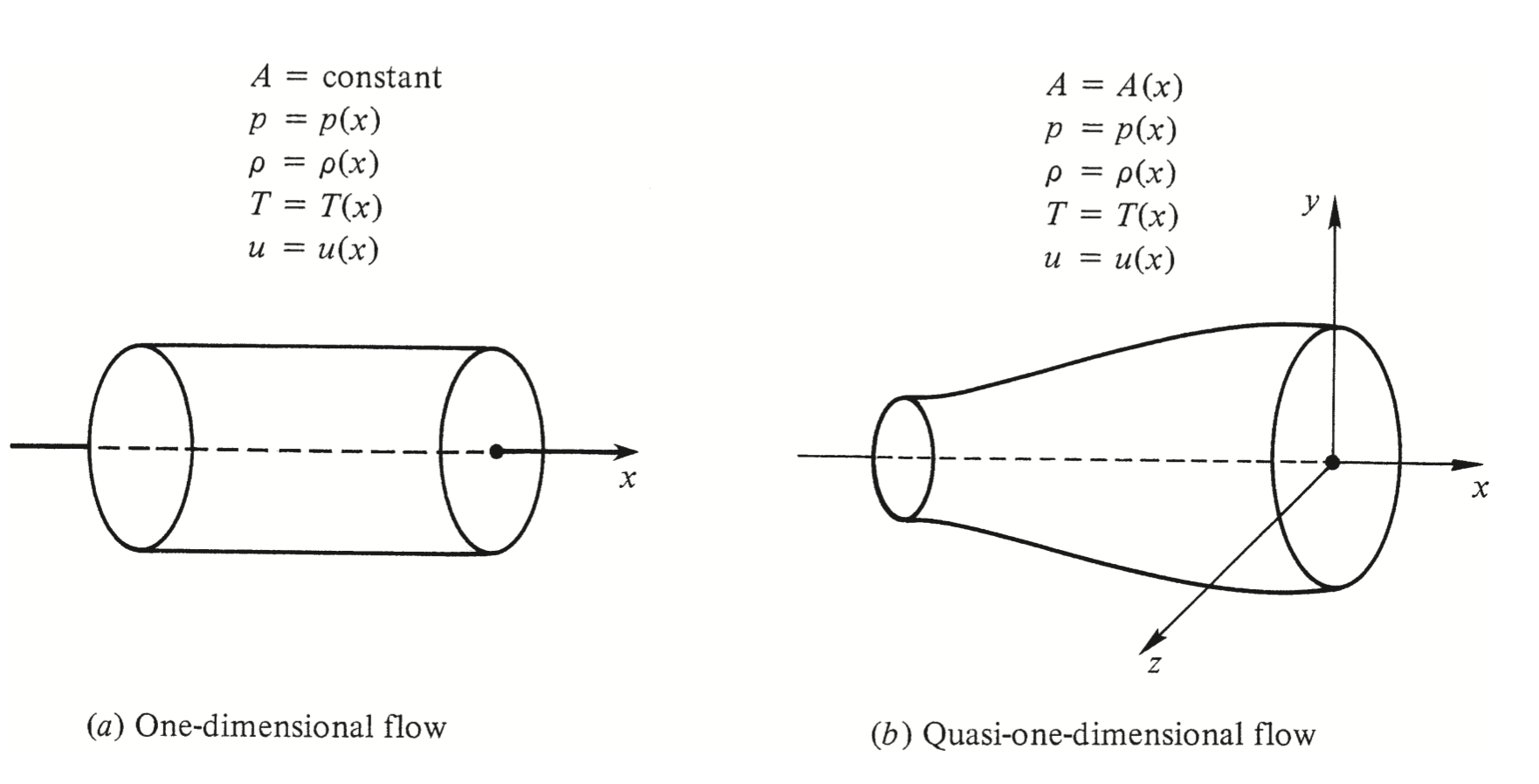

A foundational approach to fluid dynamics, particularly in high-speed regimes, begins with simplified, idealized models. These provide the necessary conceptual clarity before progressing to more complex, multi-variable flow analyses. In this chapter, we consider the most basic scenario: a flow where all physical quantities vary exclusively along a single spatial dimension.

Figure 1:In one dimensional flow, the properties in both cases vary only as function of x, and is not affected by change in y direction. In quasi one-dimensional flow, we ignore the changes along y and hence the name quasi one-dimensional flow. Anderson (1990)

J. D. Anderson, “Modern Compressible Flow with Historical Perspective,” Third Edition, McGraw Hill Professional, New York, 2003.

This modeling approach facilitates analytical treatment of various phenomena unique to compressible flows, such as shock waves and flow choking. We begin by focusing on normal shocks and how their governing relations emerge from the conservation laws under the one-dimensional assumption. Additionally, we consider flows through variable-area ducts, where despite spatial variations in cross-section, the assumption of quasi-one-dimensional flow remains a valid and useful approximation.

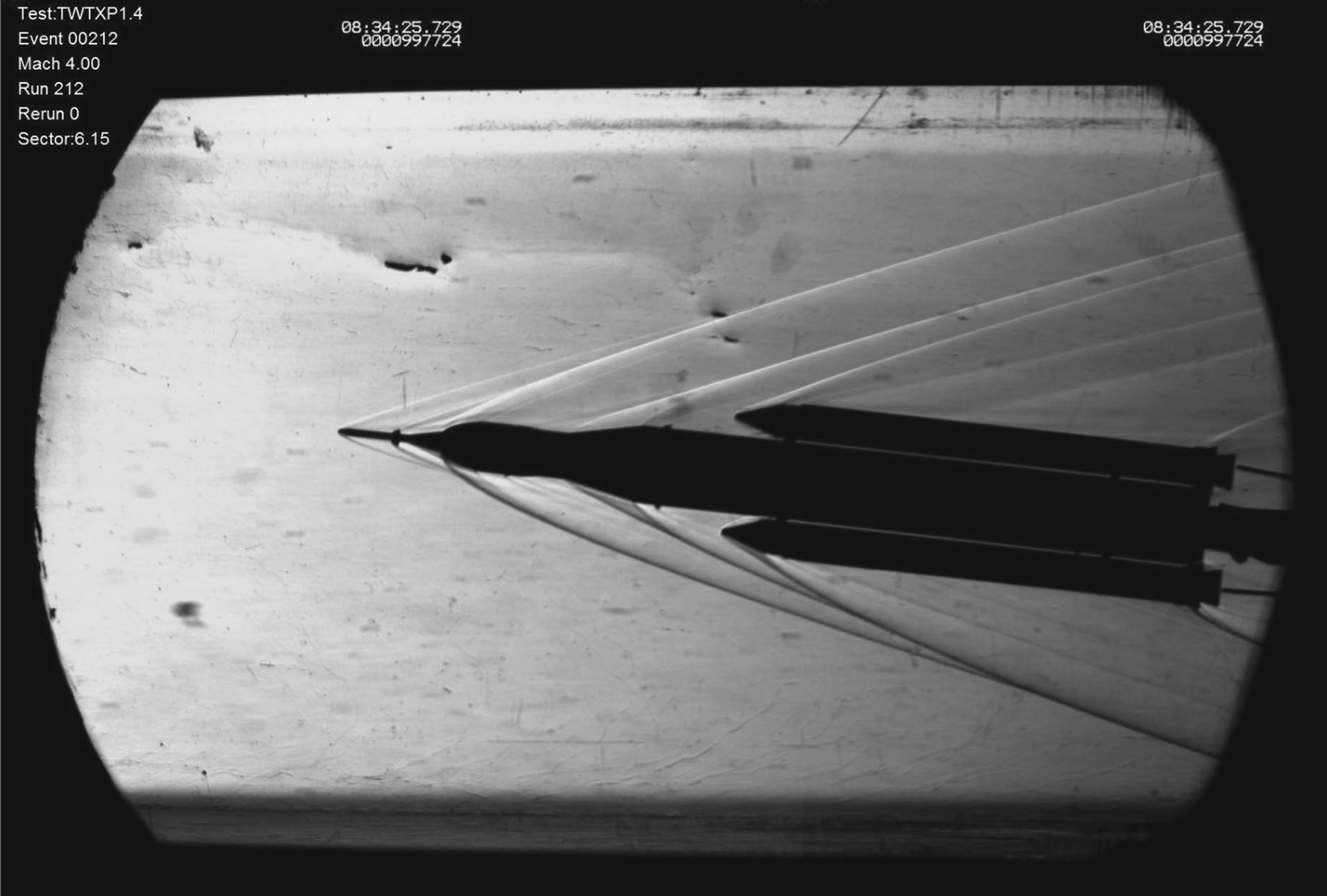

Figure 2:Observe the attached oblique shocks on the launch vehicle Anderson (1990)

J. D. Anderson, “Modern Compressible Flow with Historical Perspective,” Third Edition, McGraw Hill Professional, New York, 2003.

It is essential to first understand the physical nature of a shock wave. Consider a stationary reference frame moving with the flow velocity, under such conditions, the gas molecules appear stationary on average. Now introduce a small disturbance, such as an object entering the flow field. If the disturbance travels at subsonic speeds (i.e., below the local speed of sound), it generates pressure waves that propagate upstream, allowing the surrounding flow to respond and adjust smoothly.

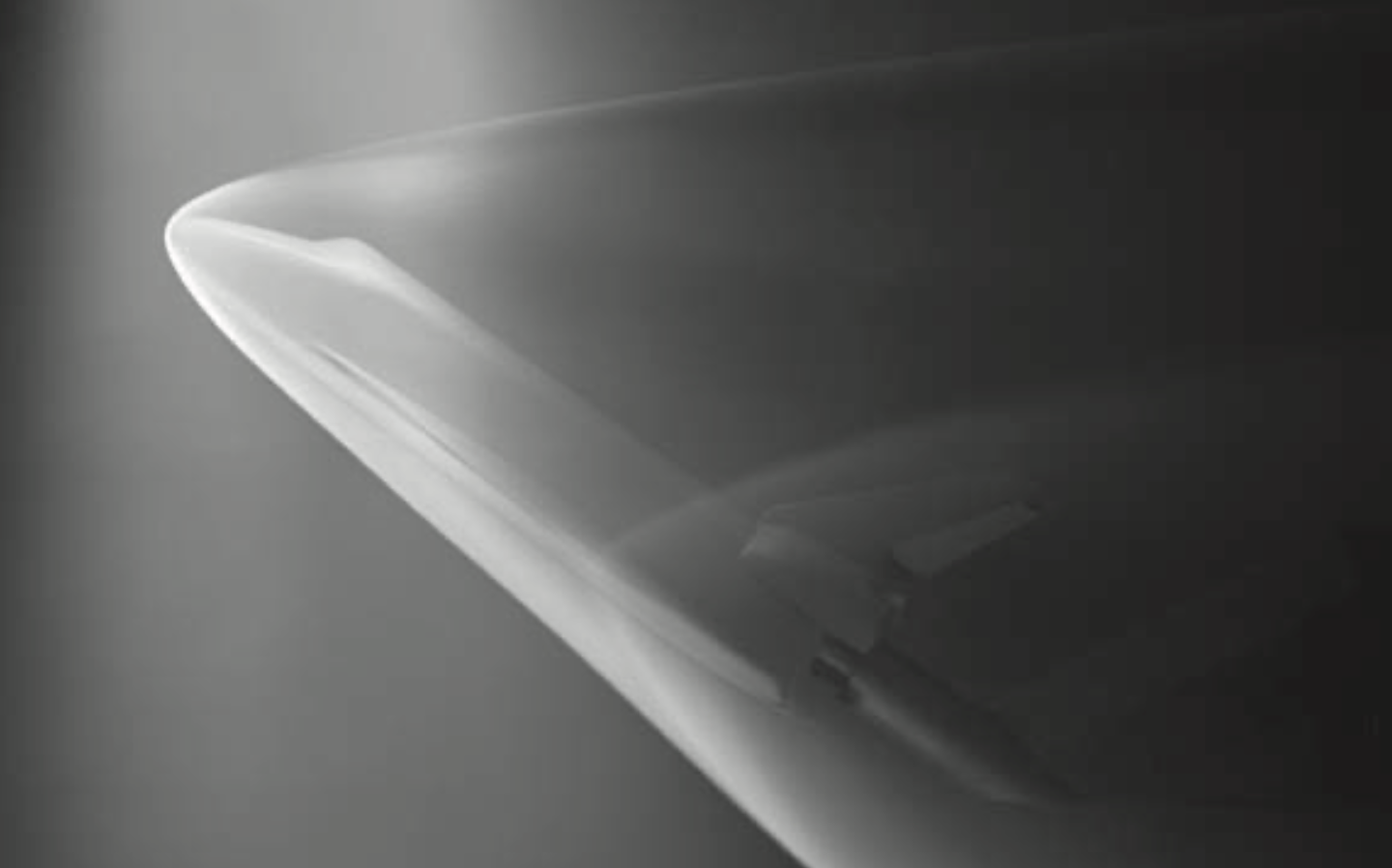

However, if the disturbance exceeds the speed of sound (i.e., becomes supersonic), the information cannot propagate upstream. The flow is unaware of the approaching object until it encounters it, leading to a discontinuous adjustment in the flow properties. This discontinuity manifests as a shock wave, characterized by abrupt changes in pressure, temperature, and density.

Figure 3:Observe the detached oblique shocks on the launch vehicle Anderson (1990)

J. D. Anderson, “Modern Compressible Flow with Historical Perspective,” Third Edition, McGraw Hill Professional, New York, 2003.

This inability of information to travel upstream in a supersonic flow lies at the heart of many unique phenomena in high-speed aerodynamics. The subsequent sections will explore the derivation of shock relations and their implications in the broader context of compressible flow theory.

- Anderson, J. D. (1990). Modern compressible flow: with historical perspective. (None).